Take-Home a Story

When you travel there’s an urge to capture everything you see with a photo, to preserve the moment, and share it with the world. But every time I did that, I noticed this huge disparity between the photo I took and what I was seeing. A photo simply cannot capture what’s unfolding in front of you. My experience was so much richer once I put down my camera and surrendered to the magic of the world. If you focus on the moment, cultivating memories and stories instead of images, you’ll return home with something so meaningful it stays with you for years to come.

https://gabriele-brown.squarespace.com/config/

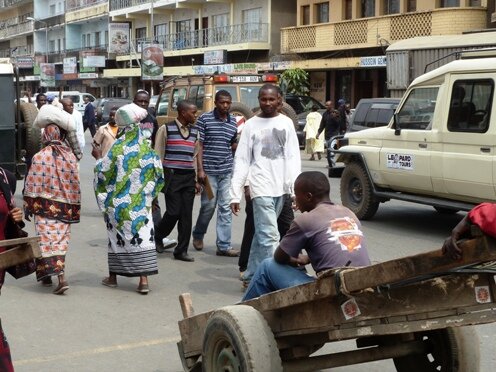

Arusha

Located exactly halfway between Cairo and Cape Town, Arusha represents the Old British Empire marked by a monumental clock tower. Dig beneath its chaotic, dusty exterior, and you’ll find there are plenty of reasons to explore this city.

Arusha’s population comprises more than 100 nationalities. It’s also a melting pot of Iraqw, Hadzabe, Maasai, Swahili, and dozens of other indigenous and ethnic cultures. Muslim and Christian communities live peacefully side by side, and locals will greet you warmly with the Swahili saying Karibu, meaning ‘welcome’.

Swahili: More Than Just a Language

Tanzania is at the cultural crossroads of Africa, the Far East, and Europe, making it a multi-lingual and multi-cultural country. And although English is widely spoken and is an official language, more people in Tanzania speak Swahili.

Swahili is a Bantu language that is spoken all the way up into Kenya and Uganda, west into Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and south into Mozambique.

As Tanzania's official language, Swahili is both the language of administration and medium of primary education and serves as a lingua franca for Bantu-speaking tribes.* This contributes significantly to the unity felt among Tanzanians. In contrast, Kenyans generally learn English in school and are taught their parents' tribal language and Swahili. If their parents come from different tribes, they are more likely to learn neither language than one or both of the tribal languages.

The interactions between Arabic traders and East Africans, spanning centuries, resulted in Arabic having a significant influence on Swahili's language. For example, the Arabic word Swahili is a "plural adjectival form of an Arabic word meaning 'of the coast'."* Although the exact number of Swahili speakers is unknown, sources report over 100 million people speak Swahili as either their mother-tongue or a second language. However, Swahili is not merely a language—Swahili culture is an inherent component of many Tanzanians' lives.

That's the theory, but what about the practice? Language and everyday culture are intertwined, so it's worth learning some polite Swahili phrases as making an effort to speak another's language is welcome in any country. But the Swahili culture has its own idiosyncrasies in what's polite and what's not. It's not just about the words you use but also the traditional social customs.

Greetings are important

Take greetings, for example. In Swahili culture, greeting etiquette is tremendously important, and it's considered very rude not to greet correctly. How you greet someone in Tanzania has an impact on how they will behave towards you. For instance, if a person doesn't greet their neighbor, they automatically dislike each other.

Respectful greetings are particularly important when interacting with elders. For example, when greeting someone older than you, you start with shikamoo (pronounced shi-ka-moh), which translates to "I touch your feet." The elder responds with marhaba, which translates to "bless you." The historical context for shikamoo takes us back to when East African residents were applying for documentation to live as residents of Tanzania. However, during the immigration process, the distinction between those who knew Swahili culture (native Tanzanians) and those who only spoke the language was made by those who started their conversations with shikamoo as a sign of respect.

Allowances are usually made for tourists, but here are some general guidelines so that you can get a good start with your Tanzanian contacts, everyone from your tour guide to your taxi driver.

Ask questions

The critical thing for a beautifully polite greeting is to spend some time asking about the person – how their health is, how their parents are, the health of their family, and how business is going. Social relationships are vital in Tanzania and sometimes life-saving, so it's essential to take the time to understand their situation and their wellbeing. Ask at least three different types of questions about their wellbeing and that of their family.

Handshakes (right hand only) are extremely important, and sometimes hands are held much longer than you might be used to – sometimes for the duration of the conversation. Your hands might meet and gently entwine fingers, and perhaps there might be some wrist-holding – there are a few variations, but don't get hung up on it. If you're respectful and friendly, no one will take offense.

Greetings practice

Learning a few of the basic Swahili phrases will help you seem even more polite and gracious to your Tanzanian hosts. Here are a few of the most useful phrases (the syllables to stress are in bold):

"Hello": "Hujambo," sometimes shortened to "Jambo." You can also use "Habari" which has a rough meaning of news (i.e., "What's the news about….?"). Use any of these, said with a smile, as you're going in for the handshake.

"Good morning!": There's nothing like a cheerful "Habari za Asubuhi!" to show friendliness and good wishes. Use "Habari za mchana" for "good afternoon".

"How are you?": Ask "Habari gani?". But if your friend gets in first with "Habari gani?" then answer: "Nzuri, Ahsante!" ("good, thanks!"). You can also say, "Poa" or "Safi!" or, if you're already on good terms, you can be less formal: "Poa, kichisi kama ndizi kwenye friji" ("I am cool like a banana in the fridge").

"Habari" – the most useful Swahili word

"Habari" is a very useful word as you can use it to say "hello," but also to ask what's the latest news. You'll impress if you ask "Habari za familia?" ("how is your family?") and follow it up with "Habari za kazi?" ("how is work?"). You can also try "Habari za kutwa?" ("how was your day?").

Other useful words

"Please": "Tafadhali"

"Thank you (very much)": "Ahsante (Sana)"

"Goodbye": "Kwaheri"

“Good night”: “Usiku mwema” or “habari za jioni”

Culturally, there is also such a thing as Swahili time—an entirely different way of telling time. In Swahili, 7:00 a.m. represents 1 o'clock, and again 7:00 p.m. means 1 o'clock. The day is divided into a.m. and p.m. but appears to follow the sun's movement, with when it rises and sets.

I am grateful for the memories I have made thus far in Tanzania and look forward to Swahili's experiences and culture to come.

If you have a smattering of Swahili and the knowledge of how to greet the locals properly, you'll be sure to charm everybody you meet.

Have the opportunity to test out your Swahili with the locals by joining me for your very own adventure to Tanzania!

“Kila jambo na wakati wake

There is an opportune time for everything”

SWAHILI TIME- AN INTERESTING CULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION

Swahili time is 6 hours different from world time! Most people realize this when they see the translation for 'one o'clock,' which in Swahili is saa saba. Saba in Swahili means' seven', so instantly, there seems to have been some sort of error. Surely 'one o'clock' should be saa moja (moja meaning 'one')? Then they see that saa moja is the translation for 'seven o'clock,' and the world starts spinning.

In Swahili, the time is measured from sunrise to sunset (daytime) and sunset to sunrise (night time). The Swahili clock determines its time according to how many hours it's been since sunrise and sunset – typically around 7 o'clock each way. This is primarily because most Swahili-speaking countries are on the equator and the times for sunrise and sunset are almost identical year-round. The sunrise in the Swahili-speaking world is so consistent that you can set your clock by it – so people do.

In Swahili Time, 1 o'clock in the morning is the first hour after sunrise (what everyone else calls 7:00 a.m.), and 1 o'clock at night is the first hour after sunset (what the rest of the world calls 7:00 p.m.).

Talking about time in East Africa, we should not forget about some habits -Even if arranged meeting days in advance, being at least 30 to 60 minutes late for an appointment is seen as the norm.

Although all say the hours in Swahili Time, no watch or clock has ever been designed especially for their way of telling time. Instead, they use standard clocks, set with the hands in the standard position, and add or subtract six hours when they read the time.

Swahili time is unofficial, sort of. Governments and schools universally measure time, along with the rest of the world. But almost every Tanzanian is also familiar with Swahili time, and some use it to organize their days. This is particularly important to remember when arranging for a taxi. If you tell the driver you need a ride to the airport and 6:00 ( in the evening), there is a good chance he will show up six hours earlier, at noon. And if you are expected for a meeting at half-past one ( meaning lunchtime), it is best to confirm the time to avoid any confusion.

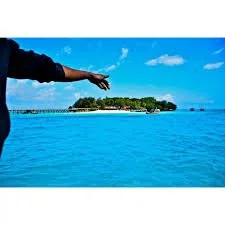

Zanzibar

The name Zanzibar has become synonymous with the exotic. Images of its white-sand beaches, azure waters, and iconic dhows plying the waters fill hearts around the world with a sense of the archipelago’s immense beauty and mystery.

Zanzibar is home to people from across the world, and it is this diversity that makes it such a unique travel destination. This cultural convergence can be seen in the diversity of the region’s food, in the polyglot nature of the Swahili language that was born here, and in the distinct architectural styles that exist side by side in Stone Town.

Zanzibar’s distinct charm results from its years of cross-cultural exchange, and it’s all the more charming for this jumble of cultures, beliefs, and languages.

The island paradise has considerably darker historic roots as a former trade and slave port during its time as a territory of the Omani Sultanate, and you can still see the Arabic influence when you’re wandering the labyrinthine alleys of historic Stone Town or in the way the Swahili language is a unique blend of local tribal languages and Arabic. You can sense Zanzibar’s Arabic roots in its bustling bazaars, its distinct architecture, and the rich spice culture that still plays a large part in the region’s economy.

This history coupled with the archipelago’s many stunning beaches, picturesque forests, and fragrant spice plantations make it a fascinating tourist destination: the kind of place where you can soak in a melting pot of cultures while also escaping to some of the world’s most beautiful beaches for a little rest & relaxation. Whether you’re visiting at the end of a safari or are coming to Zanzibar for a honeymoon, family trip, or solo beach escape – there is something for everybody on the islands that make up the Zanzibar archipelago.

What makes Zanzibar stand out from other beach destinations in the area’s rich history, with settlements in the region dating back to the 13th century on Pemba and the 14th century on Unguja.

Of course, you can go back almost 20,000 years to uncover the full depth of Zanzibar’s history. Its role as a major trade port and the colonial site makes it such a fascinating melting pot of cultures and architectural styles.

The island of Unguja was a part of the Portuguese empire from 1503 until 1698 when it fell under the sway of the Omani Sultanate, who used the island as a major port for the trade of spices as well as ivory and slaves taken from the mainland.

This Arabic influence is perhaps most evident in the architecture and culture of Stone Town, and historical sites such as the Palace of Wonders and the former slave market still stand as a testament to this time in the region’s history.

From 1890 until the islands gained their independence in 1963, the region was administered by the British Commonwealth.

With three different colonial rulers, the trade they brought from around the world, and the distinct local culture that existed before European expansion, it’s easy to see how Zanzibar has become such a melting pot of cultures and styles. You’ll find Arabic and colonial architecture on the same street while native African, Middle Eastern, Indian, and Caucasian children play together in the streets.

A visit to Zanzibar and especially Stone Town can be compared to time travel. As you wander the town’s complex network of alleys and laneways, you’re literally surrounded by history. In fact, Stone Town is a World Heritage site for precisely this reason.

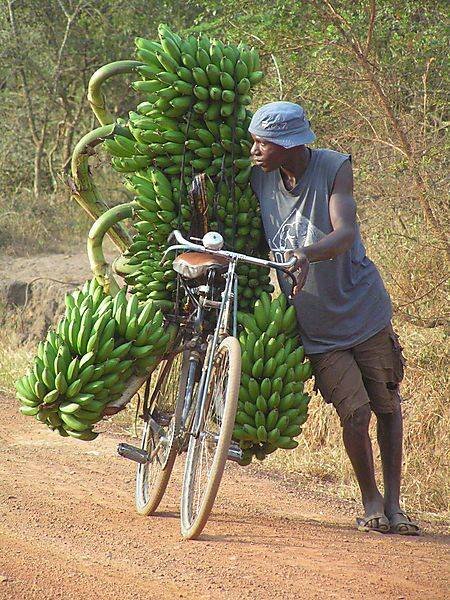

Who said bicycles are just for riding?

In Tanzania, bicycles are essential to transport all kinds of goods. I am always amazed to see what people can load onto bikes here in Tanzania. Every time I think I have seen it all, I am proved wrong.

Initially, people used bicycles to get from one place to another. Then they were used as taxis, and in towns like Tanga on the coast, there are many bicycle taxis around. This is a very cheap way to go around town and get a different perspective of the surroundings. A journey of 1-2 km will cost something like $1.

Things evolved with time, and people started transporting much more than just other people. Mto wa Mbu in northern Tanzania is known as the banana village; almost 30 different kinds of bananas are sold daily in the local markets.

That is a common sight to see people carrying up to 6 bunches of bananas on the back of their bikes, heading to the market.

Sometimes a bicycle is the only way to get products out of the farms and the markets, as roads are non-existent. Although now people are importing used mountain bikes which are suitable for off-road riding.

It is always a treat to see the new ideas some people come up with for transporting goods on bicycles. I have seen people carrying furniture, water buckets, firewood, livestock, building material, and bulk foodstuffs.

In the cities, bicycles are slowly being replaced by motorbikes. Most of the bikes come from China and India, with Phoenix being the most famous brand. Buying a new motorbike would set you back between $70 and $100. Still, bicycles play an essential role in Tanzanians day to day lives.

More and more bicycle tours are offered to tourists. This is a great way to get some exercise and have a completely new experience while visiting the country.

KANGA: A TYPE OF AFRICAN PRINT CLOTHING

Kanga Uses

Kangas are incredibly versatile and are often worn as traditional African clothing and to sleep in, wear around the house when cooking and cleaning, and carry babies in. They can also be used as curtains, mops, towels, aprons, tablecloths and are really handy to take to the beach.

The cloth is also worn by guests, or the bride, at Swahili weddings (people from the coast). The traditional ‘wedding’ kanga (called ‘kisutu’ in Swahili) is white, black, and red.

Kangas are very popular in Tanzania and Kenya. However, similar types of printed cloth can also be found in nearby countries, including Mozambique and Madagascar, where men usually wear them instead.

Kanga Sayings

Swahili proverbs were added to kanga designs at the beginning of this century. Some examples include:

Usinisumbue (don’t bother me)

Adui mpende (love your enemy)

Akili ni mali (wits are wealth)

Mtaka yote hukosa yote (one who wants all, usually loses all)

Kulekeza si kufuma (to aim is not to hit)

Sina siri nina jibu (I have no secrets, but I have an answer)

Women will wear specific Kanga to communicate a non-verbal message to their community. This form of communication, often between women, can be about personal feelings, relationships, politics, education, health, or religion.

How to wear Kanga

There are numerous ways of wearing Kanga. They can be worn as a top, skirt, shawl, cape, belt, headpiece, or even a swimsuit. The most common style is the traditional dress, which is worn like a towel or a skirt wrapped around your hips. It is common to wear more than one Kanga at a time.

We hope you have enjoyed learning about kanga cloth.

Discover Tanzania’s Heart

Tanzania, a land of superb landscapes and spectacular wildlife! But another attraction stands equally tall- the people.

Tanzania's people are among the most welcoming and approachable on earth, with a range of fascinating cultures ready to share with visitors. From the WaChagga of the slopes of Kilimanjaro to the now world-famous Maasai, a cultural excursion or more extended stay among local people is likely to become one of the most rewarding experiences of any holiday in Tanzania.

Cultural tourism programs are beneficial to everyone. The tourist gets a unique, unforgettable experience, and the local people generate income and improve their stand of living. Both parties gain a valuable understanding of another culture which will last long after the visitors have returned home.

Eyasi

Eyasi is home to some of the last hunter-gatherers in Africa, the Hadzabe. This cultural group has made the area around Lake Eyasi their long-time hunting grounds. A day trip or longer safari with the Hadzabe gives visitors a chance to experience a way of life that used to be familiar to all human societies on the planet but is now rarely practiced anywhere.

Morning hunts with the Hadzabe warriors, armed with bows and arrows, offer a fascinating glimpse into the hunter-gatherer way of life. Honey- gathering, walks to find traditional healing plants and food, and traditional dances are all part of the Hadzabe cultural tourism experience.

Maasailand

The Maasai, among the last of the world's pastoral people, adapt to the 21st century in their way and in their own time. Around 12 distinct groups of Maasai remain in the world, the largest of which now live in Tanzania. Visit Engaruka, the lost city in the shadow of the Great Rift Wall. Where Maasai mix irrigation, farming, and traditional herding. In Mkuru, near Arusha National Park, short camel treks with the local Maasai give visitors a glimpse into the nomadic culture as they climb nearby Ol Donyo Lengai.

Meru

Only minutes from bustling Arusha and centered around Africa's fifth highest peak are spots that look and feel as they did decades ago. But everywhere, too, is a transition as the WaArusha and WaMeru people adapt tradition to progress and science. Visitors can meet a traditional healer, learn about animal husbandry and agriculture, and but carving and foodstuffs from local handicraft co-operatives or women businesses.

Southern Pare Mountains

Walk the most remote mountains of northern Tanzania with local farmers through traditional Pare Village and dense tropical forest. From half-day to three-day guided hikes, this is an opportunity to step into the culture of the Pare people. Visit Mghimbi Caves, a secret hiding place during the slave raids, and proceed to Malameni /rock, the scene of Human sacrifices to appease evil spirits until the 1930s.

Usambaras

This stunning mountainous range is accessible from Lushoto in the west, home to one of Tanzanian's great historical kingdoms or Amani in the east. Today, much of the mountains are used to produce coffee, sisal, tea, and chinchona with rice grown in the swampy foothills.

Zanzibar

A tour of the heartland of Swahili culture is an excellent way for visitors to immerse themselves in the local culture and see how many Zanzibar's lives on a day-to-day basis. Learn about the many elements of the cultural fusion and cosmopolitan energy: music and dance, visual arts, traditional games, cuisine, and dhow culture, to name a few. A cultural tour is an ideal excursion for those who want a real insight into the people and life on the island and is a great way to support sustainable tourism and the people of Zanzibar.

Prison Island

In 1893 the former British prime minister of Zanzibar purchased the island and built a prison complex on it. But - it never served to its intended use! It was used as a quarantine station for yellow fever cases.

Today is the building a ruin, but it serves as a lovely guesthouse for tourists, where you'll be able to relax a bit and enjoy magnificent views after visiting the giant tortoises' reserve, where you will admire, pet, and even feed these magnificent, ancient, peaceful creatures. But - they are not locals! Four specimens of Aldabra giant tortoises were a gift from the governor of Seychelles in 1919.

They found Prison Island a great environment and bred freely. Today, many tortoises are welcoming you, and the first settlers are still among them! There is also a nursery for baby tortoises, where you can see baby tortoises of different ages. A great encounter for everyone, especially for kids!

Round up this great day with some snorkeling around the coral reefs, admire colorful fish, many beautiful starfish, and picturesque seashells., or simply relax on the white sandy beach. Upon your return admire the breathtaking view of Stone Town, the bay, and the archipelago. Prison Island is 20 minutes from Stone Town by boat and has spectacular coral reefs to enjoy while snorkelling. If you are feeling active, you can explore one of the hiking trails, snorkel in the crystal clear waters in search of colorful tropical fish darting through the reef. “Or soak up some sun on the poweder white beach.

“Shikamoo”

In the context of Tanzanians' laid-back disposition and sense of family ties and responsibilities, Tanzanians adhere to a solid social code. Emphasis is placed on manners and politeness- challenging to maintain when faced with aggressive solicitors and hustlers. Elaborate greetings are always expected.

Tanzanians value the moment of meeting, where two people catch up on recent events. Always allow adequate time to do this with friends, colleagues, clients, and civil servants, as relationships are established through continued contact. Failure to go through the expected greetings routine can result in Tanzanians perceiving you as rude, thereby decreasing their desire for collaboration,

Typically, Tanzanians greet you with a handshake- sometimes, this even inquires into your well-being and that of your family, children, home, work, and even a discussion of the past few days' events. Under normal circumstances, this greeting will follow typical lasty between three and fifteen minutes.

It is considered impolite to launch straight into the subject of your business, even if you are just asking for directions from a bystander. With strangers, the absolute minimum is a routine consisting of Jambo ( Swahili for Hello), Habari? ( How are you?), and nzufri (fine).

On the street, or in a more informal setting, you might say mambo vipi? ( slang for how are you?- a bit like how's, is it going? Or what's up?)

The answer to this is poa ( cool or good). Regardless of the reply, this is typically followed by hujambo? (problems?), the reply sijambo (no issues) and finally Karibu ( welcome), then Asante Sana ( thank you very much). When entering a home, it is customary to call our hodi and wait for the customary Karibu.

Most visitors will find greetings involve additional questions regarding their place of origin, length of stay, and destination. You might have to respond endlessly to these standard questions, but it is worth remembering that such small talk is a great opportunity for a Tanzanian to practice their English or possibly for you both to spark up a new friendship. The best receipt here is a sense of humor, patience, and a smile.

Regard for Age - Age is very important in Tanzanian culture and underpins an established societal structure. It determines social ranking in general and in the workplace, especially among women. The ages of two people meeting set the tone of the greetings. Shikamoo ( I show respect) is a greeting reserved for elders or people of stature within the community. The title babu typically follows it for an older man or bibi for an older woman.

A new employee who is younger than anyone else will often be addressed as mtoto ( child), while an older woman might be called mama( mother). Younger women address each other with Dada and guys with Kaka.

Karibu Tanzania!

The Swahili coast

The Swahili coast has seen the movement of people between the Arab world, Europe, and parts of the Indian Ocean, from as far back as the 2nd Century AD. A unique culture has evolved in East Africa, and Kiswahili - meaning “language of the coast” - is both the national language of Kenya and Tanzania and is spoken widely in Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Malawi, and Mozambique.

Swahili culture has primarily been shaped by Arabic influence, and Islam is interwoven into daily life in coastal East Africa. The sound of the adhan (call to prayer from the Mosque) permeates at dawn, and children attend madrassa (religious school). Men wear white kanzus (long robes) and women hijabs (head scarves). Many Swahili words are borrowed from Arabic, including some of the greetings and social interactions you’ll regularly hear in daily life: “Habari?” (what’s the news?); “samahani” (excuse me); “Lala Salama” (good night); “tafadhali” (please).

Poetry is prevalent, and the hypnotic sounds of traditional taarab music, with its Arabic, Persian, Indian & European influences, are distinctly Swahili in its deep coastal roots. The word “taarab” appears to derive from the Arabic verb “tariba” meaning “to be moved”. It draws heavily from the classic Egyptian orchestra ensemble incorporating the use of specific instruments such as the qanun (a type of string instrument), Middle Eastern oud, dumbek (drum), Indian tabla, violins, and cello.

Equally diverse is the unique, mildly spiced culinary style of the Swahili coast, with Indian and Arabic flavors at the forefront. Once known as the “spice island”, Zanzibar was historically part of a flourishing spice trade route and the world’s largest producer of cloves. To this day, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, and cumin seeds are some of the most commonly used ingredients, along with plenty of chili, lime, coconut, and ginger. The Indian influence is woven into delicacies such as pilau rice, samosas, biryani, and chapati. “Kahawa” is the word for coffee, from the Arabic “gahwa”, and is usually served sweet and spiced with cardamom. While masala tea - prepared using black tea leaves, cardamom pods, cinnamon sticks, ground cloves, and ground ginger - is deliciously fragrant and best enjoyed with freshly-baked mandazi, a sweet snack that resembles something between a doughnut and fried bun.

There is a huge amount of skill, pride, and adherence to tradition when it comes to the preparation of Swahili delicacies. An accomplished chef will take time to perfect their art, and each measure of spice will be perfectly apportioned. Indeed, one of my favorite chefs of all time is an older lady from Mombasa whose abilities in the kitchen are world-class. There can be few more enjoyable ways to spend an afternoon than shopping with her for fresh local produce and learning how to make the perfect chapatis, fried fish, coconut brinjal (aubergine) curry, yellow lentil dahl, and wali wa nazi (coconut rice). We offer this experience to all guests passing through Nairobi or spending time on the Kenyan coast.

Contact us at info@urthsafari.com for further details on our culinary and cultural-immersion travel experiences.

A Regional Walk Through The History of African Hair Braiding

Photo by Martin Harvey.

Zee Ngema

Maasai people. Men spend hours braiding each other long, ochred, colored hair. Near Amboseli National Park, Kenya

From West African Fulani braids to Southern Africa’s Bantu Knots, we explore Africa’s rich history and connection to hair braiding.

Hair braiding has, for centuries, been a pivotal ingredient in building identity and community and representing beauty worldwide. Interlacing three strands of hair has connected people, cultures, and ideologies, from the French’s intricate braid to the Vikings’ iteration of plaiting. Like all good things, however, strong evidence suggests that braiding originated in Africa. Researchers have traced the earliest artistic depictions of braids to the Venus of Willendorf, a 30,000-year-old female figurine found in modern-day Austria, and France’s cornrowed Venus of Brassempouy, estimated to be about 25,000 years old.

African braiding styles have dominated modern beauty trends for generations amongst Black and African communities. Where the Africans go, so too do their customs, languages, and relationships. Braiding has offered African communities opportunities to bond, develop skills, determine status, and pass down traditions, no matter where the world takes them. Though it’s a profession and fashion that tends to be dominated by women, men have had their fair share of fun throughout history. The earliest drawings of braids in Africa were found in Ancient Egypt, dating back to 3500 BC, though Namibia’s Himba people’s red, pigmented strands have been around for as long as they’ve needed to protect themselves from the sun.

Regardless of who the first braiders were or where they came from, the practice is rooted in many distinct and diverse manifestations, many of which are refashioned versions of the styles our ancestors walked around with. In this article,

North Africa

Vintage engraving of a noble of Sudan. Ferdinand Hirts Geographische Bildertafeln,1886.

Egypt’s well-maintained historical records have permitted researchers to understand their practices, including their beauty, hair rituals, and trends. Archeologists have discovered remnants of 3000-year-old weave extensions and even multi-colored hair extensions.

Hair, in Ancient Egypt, was a beauty tool used to signify status, age, and gender. Around 1600 BCE, hair braiding amongst women of royalty, nobility, and concubines was adorned with gold, beads, and perfumed grease, while common folk kept to simpler styles necessary to get work done.

In Sudan, young girls adorned mushat plaits, signifying sentimental time spent with matriarchs and illustrating femininity's poignant role in preserving culture and traditions for generations. Back then, braiding hair was considered a special ceremonial practice amongst Sudanese women, even holding the braiding “events” on specific days when female neighbors and friends were invited to partake. To prepare for matrimony, brides underwent a multi-day braid-a-thon surrounded by female friends assigned to entertain them with chatter and singing—often for two to three days at a time. Tradition called for long, silky, perfume-grease threads, as was necessary for the performance of a bridal dance crucial to the rite of the wedding program.

However, North Africa’s tendency to associate more with their Arabic heritage has made it difficult to trace their wider relationship with braiding and Afro-textured natural hair.

East Africa

Maasai people. Men commonly mix ochre and oil to color their hair and skin red. Near Amboseli National Park, Kenya.

Photo by Martin Harvey/stock photo Getty Images.

Braiding’s roots in East Africa have been traced back to 3500 BC, with cornrows (called Kolese braids in Yoruba) maintaining the top spot in popularity for just as long. In Somalia, much of the population follow the Islamic faith, and modernized adaptations of braiding are considered haram, making it a lost art. Historically, Somali women have been recorded donning long, small braids when approaching puberty.

Ethiopia has maintained an admirably close relationship with its traditional forms of braiding. In the Southwestern Omo Valley, the Hamar tribe have perfected their hairstyles to dictate male worth and female marital status. For generations, the tribes have used a mix of fat, water, and red ochre paste to congeal their dreadlocks – and heritage – into place. Former Ethiopian emperors Yohannes IV (1837 - 1889) and Tewodros II (1818 - 1868) are depicted with cornrows, further illustrating the practicality of the style amongst warriors, too.

Albaso braids, popular in Ethiopia and Eritrea, communicate and categorize different ethnicities and their role in society. The remarkable hairstyle is created with seven cornrows, braided straight back, acting as a crown in the front, and a mane of hair left to flow in the back. Ethiopia boasts a plethora of braid styles, from the Sheruba style to the Mertu style favored by the Oromo people.

The importance of braids in communicating identity is a rich part of Uganda’s history, too – and unfortunately, the influence of colonialism has had a lasting effect. During the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, enslaved Black African women had their heads shaved by colonialists in their quest to dehumanize, brutalize, and abuse. In 2016, a group of high school students in Kampala shed light on the fact that in many Ugandan schools, Black African girls are still forced to shave their heads – while their non-Black counterparts are not.

In Kenya, the Maasi and Kikuyu tribes have donned their famed matted braids, intricate beading, and gold detailings since at least 1910. Of the 43 tribes (we can account for), each one has its own signature style of wearing and braiding their hair, and those privies to the distinctions can tell which tribe you belong to by sight. However, introducing artificial hair extensions has inspired some Kenyans to venture off the beaten path.

While Tanzania’s indigenous Masai tribes have survived transitioning to professional hairdressings, some are even ex-warriors.

West Africa

Young African man from Sierra Leone dancing with plaited hair.

West Africa boasts abundant hair braiding styles, which have influenced global Black culture and trends for decades. The Fula people, whose 30 million strong population exists across West Africa, gifted the world with Fulani braids. Traditionally, the style called for five long braids fashioned into loops or left to hang to frame the face, with a coiffure braided into the center of the head. However, over time and with the modernization and globalization of communities, the braids manifest in many different ways. Fulani tribeswomen adorn their braids with silver or gold coins, beads, and cowrie shells, sometimes symbolizing wealth, status, or marital status.

In Ghana, the iconic Banana or Ghana braids have gained favor for their easy application, upkeep, and excellence in protecting natural Black hair. The introduction of hair extensions allowed Ghanaians to devise new ways of presenting the more traditional cornrow that the world has come to love, and each distinct manifestation of Ghana Braids was known to identify one’s religion and social standings. The style of braiding is easily recognizable as the front of the head is braided into small cornrows before branching out into larger braids that hang off of the head. The first examples of this way of braiding are traced back to hieroglyphics and sculptures found around 500 BC.

Similarly, Nigeria’s rich history of braiding can be traced back to a clay sculpture dated to 500 BCE depicting a cornrowed member of the Nok tribe. Like most of their counterparts, Nigeria’s unique styles of braiding are tied to the matriarchs, as they are the ones to pass the skills down through generations. The women in the Miango tribe have been known to cover their braids with leaves and scarves.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade’s role in redefining identity and culture in West Africa was arguably the most egregious. When faced with the reality of being enslaved in their own countries, the women created forms of communication and networks through cornrows and certain braids. Evidence suggests that the early fifteenth century is when communities from Wolof, Mende, Mandingo, and Yoruba tribes began to carry messages through certain braid styles.

Traces of Mali’s influence in the history of braiding are found within the Dogon tribe’s momentous archive and close ties to their original way of life. Various religious and spiritual idols depicting cornrowed spiritual leaders and the retained tradition of The Dama dance have allowed us to understand the bewildering society that contributed to our understanding of our universe.

One of Africa’s last remaining indigenous tribes, Sierra Leone’s Mende people, have maintained the same strict standards of beauty that their ancestors lived by. For Mende tribeswomen, hair is closely tied to femininity. It is juxtaposed with the way forests grow out of the Earth – the vegetation covering Mother Earth grows skyward the way Afro-textured hair grows out of the head. Hair is to be kept under tight control and styled in intricate ways to communicate beauty, sex appeal, and sanity.

Senegal’s Senegalese Twists or “Rao” as they’re known locally, came in vogue as an alternative means of creating individual, long braids – if locs or “box braids” aren’t your style. Pictures from 1884 show us that Senegalese women have stayed close to their original styles, using Yoss, dried vegetable fibers dyed black, before adopting Lebanese brand Darling Hair’s artificial hair extensions as their own. The style stands out as it’s made by mixing two strands of hair together – usually rubbed between fingers or two palms – instead of the usual three. The kinky texture of the hair extensions holds its shape for at least three months and is said to have become ingrained in Senegalese society as it mimics the action of weaving cotton rugs and more – a custom ingrained in their history.

Gambian warriors were also known to march off to war with tightly coiled braids.

Central Africa

A Mrua (Warua) man from Central Africa. Wood engraving, published in 1891.

In the heart of Africa lies a world of beauty beyond your wildest dreams. The Mangbetu people of the Democratic Republic of Congo became known for their practice of wrapping their skulls into a cone shape from infancy, locally referred to as “Lipombo.” The elongated heads were then adorned with braids plaited into a crowned basket shape called edamburu. In a testament to the wonder of the human body, the brain is unaffected by this and simply grows with the newly shaped skull. Lipombo was a status symbol among the Mangbetu ruling class – dictating beauty, power, and high intelligence.

Cameroon’s bountiful Fulani community has kept many of their hair traditions well and alive, while the region’s Bantu population participated in the popularity of the now-famed ‘Bantu knots’.

In Chad, the use of the exceptional ‘Chébé powder’ has led to generations of women with hair sure to draw envy. Women of the Basara Arab tribe are known for their thick, long, luscious hair – often plaited into waist-long individual braids. The powdered mix is made from seeds and dried vegetation indigenous to Chad and has been a staple for centuries.

Southern Africa

Portrait of a Mumuhuila teenage girl, Huila Province, Chibia, Angola on December 4, 2010 in Chibia, Angola.

Photo by Eric Lafforgue/Art In All Of Us/Corbis via Getty Images.

Southern Africa boasts an abundance of braiding styles that originated in the region. Namibia’s Himba people have gained international recognition for their age-old means of maintaining their hair. The community of pastoralists use various braiding styles – including dreadlocks – to communicate the different phases of their human experience – Young girls start out with two small braids that hang from their foreheads, until puberty, for example. Once puberty is reached, long dreadlocks are formed and covered with a mixture of goat hair, red ochre paste, and butter to foster the growth of thick, long, and luscious hair throughout their lives.

The country’s Mbalantu tribe uses eembuvi braids as an initiation into womanhood – our first examples of single braids or “box braids”. Animal fat and grounds of the omutyuula tree have young women achieving ankle-length braids by the time they hit puberty.

In Angola, asking someone to braid their hair is asking them to be friends. Among certain tribes, hair grooming was an activity trusted only by other family members — something that women were taught at a young age and encouraged to participate in throughout their lives to promote womanhood. The origins of the ever-popular Bantu Knots have been traced to the Bantu people who exist across central and Southern Africa. “Bantu” means people and was the term colonialists used to identify over 400 ethnic groups whose languages shared similar characteristics.

South Africa’s “Zulu Knots” are said to be the original manifestation of the style, donned by members of the Zulu Kingdom and its people to symbolize strength and community. As is typical within African culture, the elevated knots were considered spiritual as they were the highest point of the body. South Africa is also credited for the invention of “Box braids,” with evidence of the style being traced back to 3500 BCE. Being able to afford the time and price of the style signified great wealth, accomplishments, and more. The term “Box braids” was coined when American singer Janet Jackson rocked the style in the ’90s.

“Bao” is the Swahili word for “board”’

Have you ever played Bao? “Bao” is the Swahili word for “board”’ or “board game,” and it’s a popular game in Tanzania.

It consists of a board with two rows of pits containing seeds. The objective is to move seeds around the board and thereby take those of the opponent until he cannot move.

Bao is among the most complex mancala games in gameplay, and masters of the game are held in high regard, much like chess masters are esteemed in other parts of the world. Elders are often seen playing the game while discussing politics and other important matters at the end of the day. I recall vividly an image that recurred throughout my experiences in Tanzania: sundown at a bustling bus stand and tired old men ignoring noise and distraction so they can instead furrow their brows at seeds scattered in divots in wood, bothering to speak only if an onlooker dares challenge their strategy or if election news comes on a nearby shop's television.

Postcards from Tanzania

“Ugali”

Ugali is, without a doubt, a staple of Tanzanian cuisine. The most traditional Tanzanian food, ugali, is always present on a plate of food. But what is ugali, you may ask? At first glance, it looks like a big chunk of sticky rice, but it’s nothing like it. Ugali is made out of only two ingredients: white maize flour and water. They are stirred together until they reach a stiff consistency that pulls apart easily from the sides of the pot.

Ugali is served as a side for everything: meat or vegetable stews, beans, greens, and pretty much everything that has a sauce. Ugali is eaten with the hand, not with the fork. Simply pull a little bit apart, roll it in your hand to create a ball, and then press it with your finger in the middle to create a small indent with which you can then scoop some stew.

What does ugali taste like? In my opinion, it doesn’t really have a taste. Its role is more to fill you up rather than taste like anything.

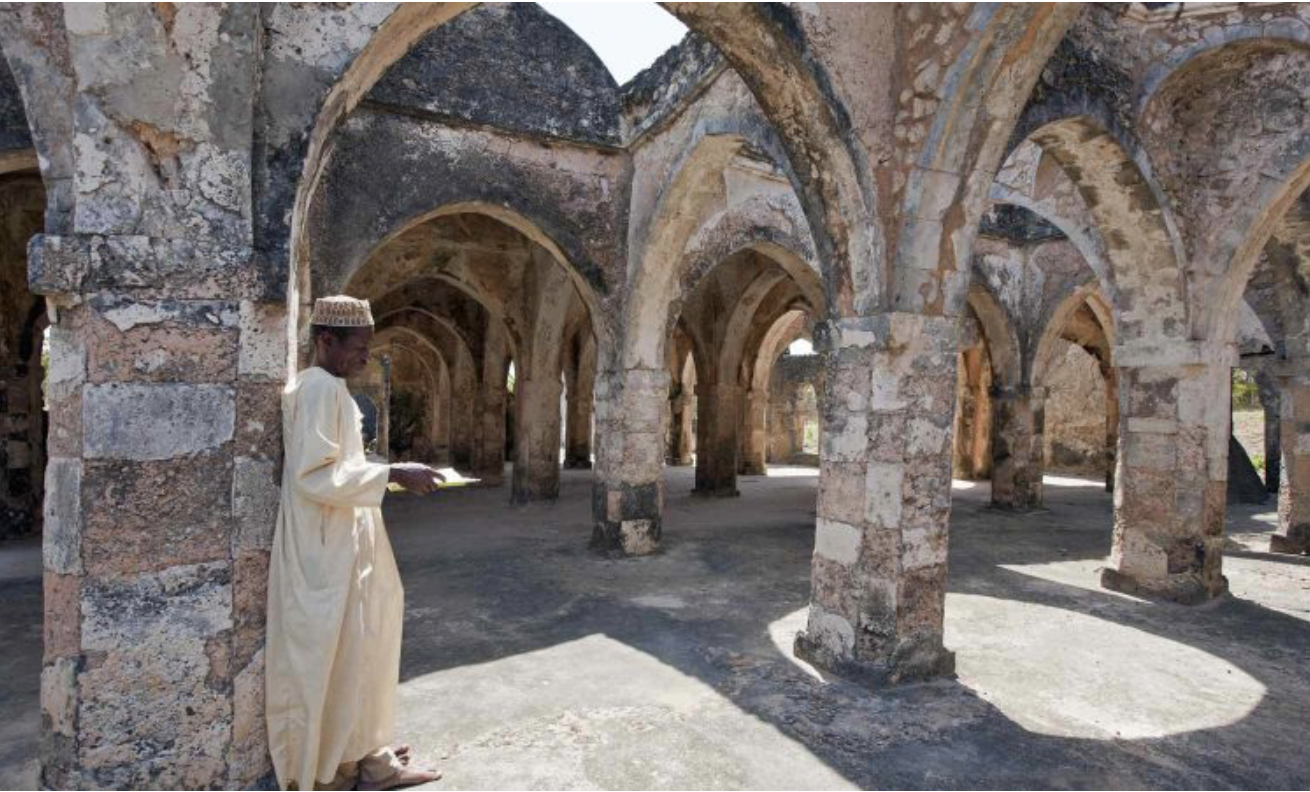

Kilwa Kisiwani, the Indian Ocean Trade, and the Rise of East African City-States

Kilwa Kisiwani, located on the southern coast of modern-day Tanzania, is a prime example of how African city-states developed and became wealthy while maintaining autonomous rule. These city-states built connections to the rest of the world while maintaining cultural, political, and economic connections with each other. Kilwa was not a lone city-state on the East African coast; there were a number of other city-states on the Indian Ocean, including Lamu, Mafia, and Zanzibar. These city-states formed the Swahili civilization and controlled the East African coast from the 9th century through the 17th and 18th centuries.

Those East African city-states started as fishing and agricultural communities. However, once agriculture created a surplus for trading, the villages became wealthier and expanded into towns and cities. The city-states enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy, each with their ruler (sultan) and complete control over the commercial activities within their territories. The city-states controlled the trade between the interior of Africa and the Indian Ocean while trading with Persia, India, China, and the Arabian Peninsula. The East African city-states constantly competed with each other over trade, and literature suggests that each city-state had its own set of dedicated traders.

The unique culture that emerged on the east coast of Africa was a result of the vibrant trade and interaction with numerous other countries. The influx of merchants from the Arabian Peninsula and Persia and the subsequent cultural harmonization with the indigenous communities gave birth to the rich Swahili culture and language. By 1930, most of these city-states had embraced Islam. Despite their cultural proximity, a homogenous Swahili kingdom never materialized, and the city-states maintained their relative autonomy, although at times, a single sultan would control more than one city-state.

Kilwa was one of the biggest and most prosperous city-states on the east coast of Africa in the 12th century. Kilwa was established as an independent city-state with political and economic rules. It had its own sultan and royal family, as well as a number of religious, political, and military officials. The set of rules that governed the island was inspired by Islam, the main religion on the island at that time. The culture in Kilwa, like most East African city-states, was cosmopolitan. The people spoke Swahili, practiced Islam, and interacted with Arabs and Persians to create a unique regional culture.

Kilwa, with its heavy reliance on the Indian Ocean trade, emerged as one of the largest and most prosperous city-states on the east coast of Africa in the 12th century. Kilwa traders dealt with valuable commodities such as ivory, gold, and even slaves while importing luxury goods like glass, silk, and porcelain. The ambitious Sultans of Kilwa sought to expand their influence over regional trade routes, gaining political control over other Swahili towns like Mvita (Mombasa), Zanzibar, and even across the Mozambique Channel in Mas control over gold mining in Zimbabwe further solidified its dominance over the trade routes of and up to the Red Sea, enhancing the Indian Ocean its power and ’ its power and wealth.

Kilwa’s wealth attracted the Portuguese to the city, who took control of the city-state after besieging it in the 16th century. Consequently, the Omani rulers of Zanzibar, as well as the French, took control of the Kilwa island. From that point on, Kilwa’s trade started shrinking, and the city went into decline. In the 19th century, the city was abandoned until it became part of the German East Africa Colony from 1886 until 1918.

Kilwa and other East African city-states demonstrate the universality of the city-state as centers of trade and commerce. The power of pre-colonial Kilwa and its place as a commercial entrepot are still evident in the ruins left throughout the island today. Monuments of Kilwa’s cultural and political influence, like the Great Mosque of Kilwa and the Palace of Husuni Kubwa, still stand. The influence of Kilwa on the unique Swahili culture throughout the region remains clear.